THE SHEN, YI AND ZHI AND NEEDLING IN THE NEI JING

THE SHEN, YI AND ZHI AND NEEDLING IN THE NEI JING

The Nei Jing, and especially the Ling Shu, contains very many passages with instructions to acupuncturists as to how to needle. All these passages give instructions as to how to engage the Shen, Yi or Zhi (of the practitioner) when needling.

Just as a reminder, Yi is the mental faculty of the Spleen which refers to “focusing”, “attention”, “concentrating”, “idea”. Its character is based on the Heart radical which means that this mental faculty relies on the overlapping natures of Yi and Shen (and therefore Spleen and Heart).

意 Yi

心 Xin (heart)

心 Xin (heart)

Zhi of the Kidneys refers to “will power”, “intention”, “resolve”, “commitment” but also “memory”, “will”. Its character is based also on the heart radical together with the character for “Shi” which means scholar, soldier, gentleman, person trained in certain field, general, officer.

志 Zhi

士 Shi (scholar, soldier, gentleman, general, officer)

士 Shi (scholar, soldier, gentleman, general, officer)

What is evident from all these passages is that the results one gets depend on the skill and sensitivity of the acupuncturist deriving from his or her Shen, Yi and Zhi. They are therefore very subjective: two acupuncturists may use the same points but the results may vary depending on the subjective application of the mental faculties of Shen, Yi and Zhi.

Ling Shu, chapter 1

“When holding the needle [literally “the Dao of holding the needle”], it should be held straight and not slanting to left or right. The [acupuncturist’s] Shen should be on the tip of the needle and his/her Yi on the disease.” Some translate the last few words as “the acupuncturist should concentrate his/her mind at the needle point and take good notice of the patient”. They therefore interpret the word bing, which means “disease”, as bing ren which means “patient”.1

Another source translates this as “When inserting the needle, the doctor should concentrate his mind on the patient.” Both these translations sound plausible but both miss the clear reference of the original to text to Shen and Yi as two separate mental faculties. Shen zai qiu hao, shu Yi bing zhe.2

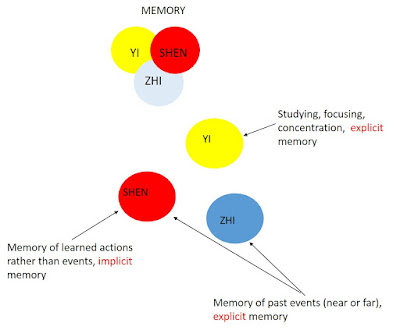

Both these translations miss the beautiful idea that the “Shen should be on the needle and the Yi on the disease.” This makes complete sense if we consider that the Shen, besides cognition, is responsible for what we might call “muscle memory”. Shen, Yi and Shi, all three are responsible for memory but the Shen is responsible for “intrinsic” memory, i.e. for example remembering how to sew or ride a bike as opposed to remembering events, numbers, names, etc.

Thus, the Shen being on the tip of the needle refers to the skill, sensitivity and concentration of the acupuncturist. On the other hand, the Yi is responsible also for concentration, but also focusing, cognition, studying. That the Yi should be “on the disease” is a reference to the necessity of a laser-like diagnosis, pathology and treatment of the disease. Our acupuncturist’s skill would be for nothing if our diagnosis and treatment are wrong.

Ling Shu, chapter 9

“Concentrate the Shen on one point and the Zhi on the needle.” Notice the distinction between the Shen and the Zhi, similar to that between Shen and Yi of chapter 1. This distinction is completely lost in a modern Chinese translation: “Concentrate the attention and focus the whole mind on needling.”3

This statement is in the context of the description of the optimum conditions for needling a patient. “Acupuncturists should be in an isolated quite place, carefully observing the mental state [of the patient], close all doors and windows, tranquilize the mind, concentrate the attention.”

What they translate as “tranquilize the mind” is actually “so that Hun and Po are not scattered”; and what they translate as “concentrate the attention” is actually “focusing on Yi and concentrating the Shen”.

Ling Shu, chapter 8

The famous chapter 8 of the Ling Shu (entitled Ben Shen) is frequently quoted, especially its famous opening sentence. I would like to comment briefly on that sentence and propose a different translation of it.

The famous chapter 8 of the Ling Shu (entitled Ben Shen) is frequently quoted, especially its famous opening sentence. I would like to comment briefly on that sentence and propose a different translation of it.

The opening sentence of chapter 8 of the Ling Shu is: Fan ci zhi fa, xian bi ben yu shen 凡 刺 之 法 先 必 本 于 神 and the words mean literally “every needling’s method first must be rooted in Shen”. This sentence is usually translated as: “All treatment must be based on the Spirit”. The implication of this sentence is that all treatment must be based on the Spirit (of the patient), whatever interpretation we give to the word “Spirit”.

I propose an alternative translation with two important differences. Firstly, the text uses the word ci which means “to needle”, not “to treat”. If the text had meant to use the term “to treat”, it would have used the word zhi which does occur a lot in both the Su Wen and the Ling Shu. Thus, the first difference is that the first half of the sentence is “when needling” rather than “when treating”: this is an important difference.

The second difference is that the “Shen” referred to here may be interpreted as the Shen of the practitioner, not of the patient. Therefore, the whole sentence would mean: “When needling, one must first concentrate one’s mind [Shen]”. If that “Shen” is the Shen of the practitioner, then “Mind” would be a better translation here.

This interpretation is consistent with two factors. Firstly, the Ling Shu is very much an acupuncture text and therefore the reference to concentrating when needling makes sense. Secondly, the advice to concentrate and focus when needling is also found in many other places in the Nei Jing. Indeed, the word “shen” is even used occasionally to mean “needling sensation”. Chapter16 of the Su Wen says: “In Autumn needle the skin and the space between skin and muscles: stop when the needling sensation [shen] arrives.”

There are many passages in both the Ling Shu and Su Wen that stress the importance of concentrating one’s mind when needling. Indeed, chapter 25 of the Su Wen contains a sentence that is almost exactly the same as the opening sentence of the famous chapter 8 of the Ling Shu. Chapter 25 of the Su Wen contains this sentence: “fan ci zhi zhen, bi xian zhi shen”. 凡 刺 之 真必 先 治 神]. I would translate this so: “For reliable needling, one must first control one’s mind [shen].” Note the beautiful rhyming of “zhen” with “shen”.

The English translation of the Su Wen by Li Zhao Guo simply translates this sentence as “The key point for acupuncture is to pay full attention.”4 My interpretation is corroborated by the other paragraphs in that chapter which give advice as to how to practice needling. In fact, it says that the acupuncturist should not be distracted by people around or by any noise.

Unschuld, in his new translation of the Su Wen, translates this sentence as “For all piercing to be reliable, one must first regulate the spirit.”5 This translation would contradict mine but a footnote in the same book reports the interpretation of Wang Bing (the editor of the Nei Jing): “One must concentrate one’s mind and be calm without motion. This is the central point of piercing.”6 Notice that Unschuld says “piercing” and not “treating.”

Su Wen, chapter 54

This chapter has similar recommendations about concentrating while needling. It says: “Do not dare to be careless, as if one looked down into a deep abyss. The hand must be strong as if it held a tiger. The spirit [Shen] should not be confused by the multitude of things, that is have a tranquil mind [Zhi] and observe the patient, look neither to the left nor to the right.”7

This chapter has similar recommendations about concentrating while needling. It says: “Do not dare to be careless, as if one looked down into a deep abyss. The hand must be strong as if it held a tiger. The spirit [Shen] should not be confused by the multitude of things, that is have a tranquil mind [Zhi] and observe the patient, look neither to the left nor to the right.”7

After this passage, the text says that “one [the acupuncturist] must have a positive mind [Shen] by looking into the patient’s eyes and control his/her mind [Shen] so that Qi flows smoothly.”8

The modern Chinese translation of this passage is “To keep the mind [of the patient] concentrated means to prevent [the patient] from distracting his or her attention so as to make Qi flow smoothly.” The translator here takes the first reference to “shen” as the Shen of the patient while I interpret it as the Shen of the practitioner that must be concentrated.

Note how all meaning is lost when the Chinese medicine terms are translated. The distinction between Shen, Yi and Zhi when concentrating in needling is lost when these are translated as “attention”; or translating “so that Hun and Po are not scattered” as “tranquilizing the mind”; or translating “focusing on Yi and concentrating the Shen” as “concentrating the attention”; or translating the beautiful expression “the Shen on the tip of the needle and the Yi on the disease” as “when inserting the needle the doctor should concentrate his mind on the patient”; or translating “Jing-Shen not focused and Zhi and Yi not logical” as “cannot concentrate mind or make logical analysis”9; or “when the essence spirit is not concentrated and when the mind lack understanding”10.

As for the translation of “Shen” as “spirit” or “mind”, that would require a long dissertation. Suffice to say that in all these passages “Shen” refers to “concentration”, “analysis”, “focusing”. “attention” and therefore “mind” would be a better translation of it.

Acupuncture and shamanism

Shamanism was the form of healing prevalent in China before the Warring States Period (476-221 BC). Disease was caused by invasion of evil spirits (gui) and healing was performed by shamans reciting incantations. Shamans used to do this also fending the air with arrows and spears.

Shamanism was the form of healing prevalent in China before the Warring States Period (476-221 BC). Disease was caused by invasion of evil spirits (gui) and healing was performed by shamans reciting incantations. Shamans used to do this also fending the air with arrows and spears.

The character for “medicine” (Yi) in use before the Warring States Period is made up of the radicals for “ancient weapon made of bamboo” (shu), “quiver of arrows” (yi) and “shaman” (wu). During the Warring States Period the radical for “shaman” in the pictograph of “medicine” was replaced by the radical for herbal decoction: the shaman had been replaced by the herbalist.

医 quiver of arrows

殳 bamboo weapon

巫 shaman

穴 cave, acupuncture point (xue)

殳 bamboo weapon

巫 shaman

穴 cave, acupuncture point (xue)

Evil spirits used to reside in “caves” called xue which is the same character as “acupuncture point”. I am of the opinion that shamanism was the origin of acupuncture: I think it is a short step between fending the air with an arrow to drive out evil spirits and actually piercing the body to drive out evil spirits from the “caves” in the body. I stress this is only my intuition and I have never read any corroboration of it.

The early connection between shamanism and acupuncture in my opinion is mirrored in the many Nei Jing passages describing the skill, intuition and sensitivity of the acupuncturist depending on his/her Shen. We are not shamans but there is a “shamanistic” quality to acupuncture, it is an art and it is very subjective.

I have noticed this also when I would get excellent results and the patient would feel very much better: whenever I repeated that same acupuncture treatment, it never yielded the same results because the conditions of the first treatment (influenced by subtle, subjective factors due to my Shen and its interaction with the patient’s Shen) could not be reproduced.

It is interesting that during the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127) there was a strong movement towards establishing medical schools and editing the classics of Chinese medicine (the Nei Jing was edited three times by imperial committees). As part of this “clean-up” of medicine, there was a drive towards eliminating shamans and the shamanism that was prevalent in the South.

During the Northern Song dynasty, southerners’ medical customs and reliance on shamans were considered almost “barbaric” usually in a degree increasing with their distance from the northern centre. Their deities were labelled “demons” (gui), their religious officiants were labelled shamans (wu) and their healing practices were described as noxious.11

Song officials’ concern focused on the southerners’ preference for local shamans over physicians which was seen as the root of their ignorance of medicine. In some prefectures, prefects even forced shamans to change occupation and apply themselves to acupuncture! Their shrines were destroyed.12

If acupuncture has indeed shamanistic qualities (much more than herbal medicine), it may explain the difficulties of conducting acupuncture clinical trials. An acupuncture treatment is subject to very many variables, to the subjective state of the practitioner’s Shen, to the interaction with the patient’s Shen, to the intent, skill and sensitivity of the acupuncturist, all of which may make it difficult to conduct clinical trials, especially if they are based on a standard acupuncture “prescription”. Even in modern China, acupuncture doctors teach about directing the needling sensation simply with the power of Shen. For example, in Nanjing they taught us that, in order to direct the needling sensation downwards along a channel, we should press with the thumb behind the point and visualize with our Shen the downward movement of Qi along the channel.

END NOTES

1. Wu N L, Wu A Q Yellow Emperor’s Canon of Internal Medicine, China Science and Technology Press, Beijing, 1999, p. 495.

2. Li Z G, Liu X R, Yellow Emperor’s Canon of Medicine - Spiritual Pivot, World Publishing Corporation, Xi’an, 2008, p. 9.

3. Ibid., p. 179.

4. Li Zhao Guo (translator) Yellow Emperor’s Canon of Medicine, Library of Chinese Classics, World Publishing Corporation, Xi’an, 2005, p. 335.

5. Unschuld P U and Tessenow H, Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen – An Annotated Translation of the Huang Di’s Inner Classic – Basic Questions, Vol. I, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2011, p. 428.

6. Ibid., p. 428.

7. Unschuld, p. 19.

8. Li Zhao Guo (translator) Yellow Emperor’s Canon of Medicine, Library of Chinese Classics, World Publishing Corporation, Xi’an, 2005, p. 601.

9. Ibid., p. 1261.

10. Unschuld, p. 681.

11. Hinrichs T J, Barnes L L, Chinese Medicine and Healing, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2013, p. 109.

12. Ibid., p. 109.

1. Wu N L, Wu A Q Yellow Emperor’s Canon of Internal Medicine, China Science and Technology Press, Beijing, 1999, p. 495.

2. Li Z G, Liu X R, Yellow Emperor’s Canon of Medicine - Spiritual Pivot, World Publishing Corporation, Xi’an, 2008, p. 9.

3. Ibid., p. 179.

4. Li Zhao Guo (translator) Yellow Emperor’s Canon of Medicine, Library of Chinese Classics, World Publishing Corporation, Xi’an, 2005, p. 335.

5. Unschuld P U and Tessenow H, Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen – An Annotated Translation of the Huang Di’s Inner Classic – Basic Questions, Vol. I, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2011, p. 428.

6. Ibid., p. 428.

7. Unschuld, p. 19.

8. Li Zhao Guo (translator) Yellow Emperor’s Canon of Medicine, Library of Chinese Classics, World Publishing Corporation, Xi’an, 2005, p. 601.

9. Ibid., p. 1261.

10. Unschuld, p. 681.

11. Hinrichs T J, Barnes L L, Chinese Medicine and Healing, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2013, p. 109.

12. Ibid., p. 109.

Comments

Post a Comment